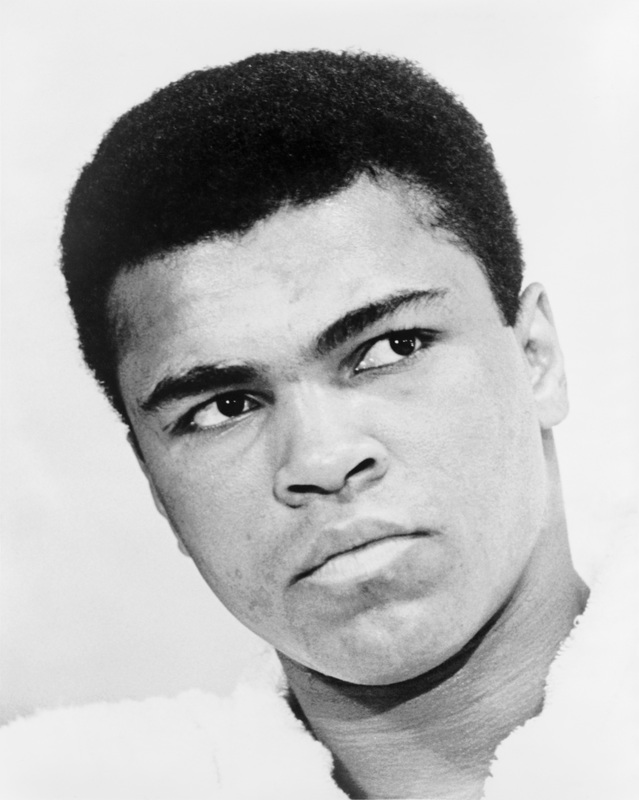

When the news was out, Ali had died, my son, Alex, texted me. "RIP, Ali." He was in Philadelphia three times zones away with friends. I was out to dinner with an old newspaper colleague in Oakland's Jack London Square. "You should write something," he said.

The New York Times, where I have worked for 25 years, had already summoned a lineup of sports writing legends, who had traveled the globe with Ali, chronicling the historic fights of a man who didn't need 21st Century connectivity to become the world's most famous athlete, or person. Dave Anderson. Bob Lipsyte. George Vecsey. I had the privilege of working with all three before they retired. Now I look around at the N.B.A. finals at all the ambitious, talented journalists two and three decades younger than I am. I was an adolescent fan-boy when Ali was dancing in his prime. Near the end of his career, I broke into the newspaper business covering another sport. Never did see him fight live.

Still, Alex insisted, "You grew up with him."

Yes, the fight night memories of sitting around the kitchen table in my family's apartment in Staten Island's West Brighton Houses are fond ones, my dad fiddling with with the dial, locating the fight, allowing me to stay up past my school night bedtime. He was no great sports fan and certainly no Ali fan, repelled by the self-aggrandizement. Like so many young baby boomers, I couldn't resist him, couldn't imagine a more compelling athlete, and that was long before he put a face on a generation in contempt of a most sinful war.

The 1965 night Ali fought Sonny Liston in a rematch of the bout in which he'd taken Liston's title, I lingered in the bathroom too long. My father yelled out, "The fight is starting." By the time I'd finished my business and walked into the kitchen, he was unplugging the radio. "Go to bed," he said. "It's over." He didn't look happy. The kid with the big mouth had won, a knockout in round one, after Dad had predicted that Liston would "give it to him good."

I became fascinated with that fight, staged in Lewiston, Maine, which I had never heard of. Wasn't championship boxing an event for smoke-filled arenas in great urban centers? Why there, in the middle of nowhere? Fifty years later, my curiosity not satiated, I drove up to Lewiston, spent a few days, looking for the story of the fight, finding along with it the great symbolism it held for the city.

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/20/sports/the-night-the-ali-liston-fight-came-to-lewiston.html

I learned that the fight had landed in Lewiston because a Massachusetts district attorney, fearing for its legitimacy, had pulled the plug on staging it in Boston Garden less than a month before the settled date. The promoters needed a site to preserve a new revenue stream, the miracle of closed circuit television. They would have held it in a corn field, if necessary, and practically did.

I would later watch Frazier beat Ali in their epic first Madison Square Garden fight a mile away, at a theater on 14th St. Then Ali and Foreman from Kinshasa, Zaire at an old movie house, the Paramount on Bay St., in Staten Island. And somewhere in Brooklyn, an Ali-Norton bout from Yankee Stadium with my dad, who argued bitterly on the drive home that they'd stolen the decision from Norton because Ali was the meal ticket.

Alex was born in November 1989. My dad died seven months later, not long after I had taped Buster Douglas's knockout of Mike Tyson for him and watched it with him when he and my mother were over to babysit one Saturday night. He sat on the couch, holding Alex, while we reminisced about the old Ali fights. Was something passed down that night, grandfather to grandson, while I experienced what was one of the last happy memories of my father alive?

From his toddler days of dribbling a miniature basketball around the apartment in Chicago Bulls wear, plastic red glasses (a la Horace Grant) sliding down his nose, Alex was always an unusually astute young sports fan. Some of his early bedtime stories actually came from NBA team yearbooks. Later, he moved on to more traditional narratives, including a book of retrospectives from Ali opponents. We read a chapter a night, each perspective so different, so savored. Around that time, the 2001 biopic starring Will Smith hit the theaters. Alex was in middle school. I took him to see it. He loved the ending, Ali on the ropes, in the Kinshasa rain, arms raised in triumph.

At home, whenever we would stumble upon an old Ali classic -- the real Foreman fight, anything from the Frazier trilogy -- we would curl up on the couch.

Alex was still texting me hours after the Ali announcement, two a.m. back east Saturday morning, urging me to write something.

Some of his texts:

"The most important athlete ever."

"He was part of what we learned in school, much bigger than sports."

"He's the only athlete that can top Jordan for me."

I asked him: "What are you still doing awake?"

He texted back: "This is too important. I was born in '89 and I feel the impact."

Before we signed off, he said: "You raised me right," his appreciation for my helping him understand the magnitude of the man.

I fell asleep thinking, thank you, Ali, for connecting the generations of your lifetime, and presumably, hopefully, many more to come.

The New York Times, where I have worked for 25 years, had already summoned a lineup of sports writing legends, who had traveled the globe with Ali, chronicling the historic fights of a man who didn't need 21st Century connectivity to become the world's most famous athlete, or person. Dave Anderson. Bob Lipsyte. George Vecsey. I had the privilege of working with all three before they retired. Now I look around at the N.B.A. finals at all the ambitious, talented journalists two and three decades younger than I am. I was an adolescent fan-boy when Ali was dancing in his prime. Near the end of his career, I broke into the newspaper business covering another sport. Never did see him fight live.

Still, Alex insisted, "You grew up with him."

Yes, the fight night memories of sitting around the kitchen table in my family's apartment in Staten Island's West Brighton Houses are fond ones, my dad fiddling with with the dial, locating the fight, allowing me to stay up past my school night bedtime. He was no great sports fan and certainly no Ali fan, repelled by the self-aggrandizement. Like so many young baby boomers, I couldn't resist him, couldn't imagine a more compelling athlete, and that was long before he put a face on a generation in contempt of a most sinful war.

The 1965 night Ali fought Sonny Liston in a rematch of the bout in which he'd taken Liston's title, I lingered in the bathroom too long. My father yelled out, "The fight is starting." By the time I'd finished my business and walked into the kitchen, he was unplugging the radio. "Go to bed," he said. "It's over." He didn't look happy. The kid with the big mouth had won, a knockout in round one, after Dad had predicted that Liston would "give it to him good."

I became fascinated with that fight, staged in Lewiston, Maine, which I had never heard of. Wasn't championship boxing an event for smoke-filled arenas in great urban centers? Why there, in the middle of nowhere? Fifty years later, my curiosity not satiated, I drove up to Lewiston, spent a few days, looking for the story of the fight, finding along with it the great symbolism it held for the city.

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/20/sports/the-night-the-ali-liston-fight-came-to-lewiston.html

I learned that the fight had landed in Lewiston because a Massachusetts district attorney, fearing for its legitimacy, had pulled the plug on staging it in Boston Garden less than a month before the settled date. The promoters needed a site to preserve a new revenue stream, the miracle of closed circuit television. They would have held it in a corn field, if necessary, and practically did.

I would later watch Frazier beat Ali in their epic first Madison Square Garden fight a mile away, at a theater on 14th St. Then Ali and Foreman from Kinshasa, Zaire at an old movie house, the Paramount on Bay St., in Staten Island. And somewhere in Brooklyn, an Ali-Norton bout from Yankee Stadium with my dad, who argued bitterly on the drive home that they'd stolen the decision from Norton because Ali was the meal ticket.

Alex was born in November 1989. My dad died seven months later, not long after I had taped Buster Douglas's knockout of Mike Tyson for him and watched it with him when he and my mother were over to babysit one Saturday night. He sat on the couch, holding Alex, while we reminisced about the old Ali fights. Was something passed down that night, grandfather to grandson, while I experienced what was one of the last happy memories of my father alive?

From his toddler days of dribbling a miniature basketball around the apartment in Chicago Bulls wear, plastic red glasses (a la Horace Grant) sliding down his nose, Alex was always an unusually astute young sports fan. Some of his early bedtime stories actually came from NBA team yearbooks. Later, he moved on to more traditional narratives, including a book of retrospectives from Ali opponents. We read a chapter a night, each perspective so different, so savored. Around that time, the 2001 biopic starring Will Smith hit the theaters. Alex was in middle school. I took him to see it. He loved the ending, Ali on the ropes, in the Kinshasa rain, arms raised in triumph.

At home, whenever we would stumble upon an old Ali classic -- the real Foreman fight, anything from the Frazier trilogy -- we would curl up on the couch.

Alex was still texting me hours after the Ali announcement, two a.m. back east Saturday morning, urging me to write something.

Some of his texts:

"The most important athlete ever."

"He was part of what we learned in school, much bigger than sports."

"He's the only athlete that can top Jordan for me."

I asked him: "What are you still doing awake?"

He texted back: "This is too important. I was born in '89 and I feel the impact."

Before we signed off, he said: "You raised me right," his appreciation for my helping him understand the magnitude of the man.

I fell asleep thinking, thank you, Ali, for connecting the generations of your lifetime, and presumably, hopefully, many more to come.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed