If Julius Erving was determined to make one thing clear in the recently premiered NBA-TV documentary titled "The Doctor," it seemed to be the notion that he glances back on his storied career with no regrets -- but mostly looks forward to the remaining days of life.

There was a time years ago when I wondered about that. It was during the 1996 NBA finals, first at a press conference to announce the coming celebration of the league's 50th anniversary season. Erving attended, with Commissioner David Stern, who mentioned the Doctor as a prime example of how current players should better understand the role that former stars had played in establishing opportunities for wealth and fame.

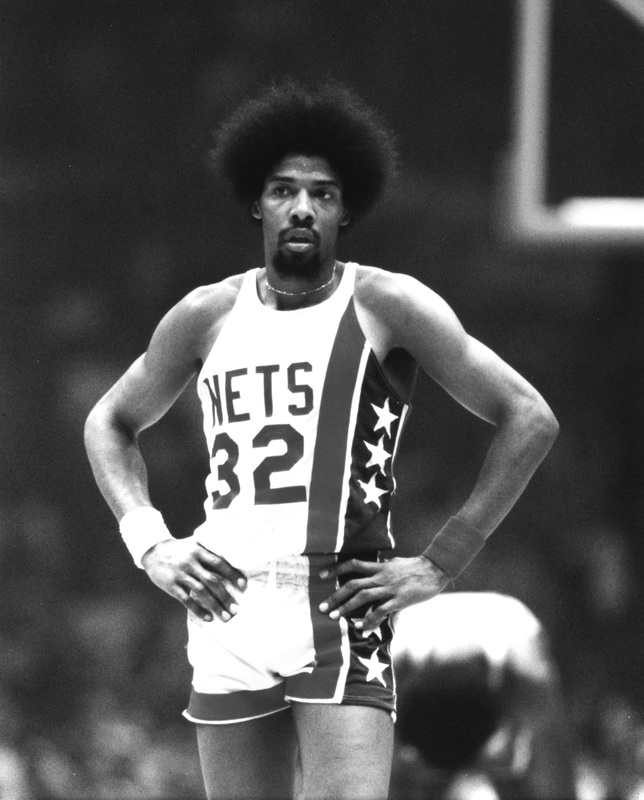

In concurring, Erving wondered aloud why ABA stats were not part of the NBA record book and proceeded to list his many achievements with the Virginia Squires and New York Nets. It all seemed in good spirits until Erving carried on too long and those of us in the audience were left with the impression that he was not at all a man at peace.

It was understandable if he wasn't. Had he been born a decade later, Erving would have been a major part of the global expansion, the Dream Team phenomenon, a charismatic and electrifying co-star with Michael, Magic and Larry in taking the world by storm.

Later during the '96 finals, I happened upon a post-game meeting in the United Center tunnel between Jordan and Denzel Washington. As individuals, those two had transcended African-American typecasting, appealing to a wide swath of consumers. In tandem, they reflected the blurring of entertainment and sports. It was as if two powerful heads-of-state had by chance bumped into each other and caused a scene.

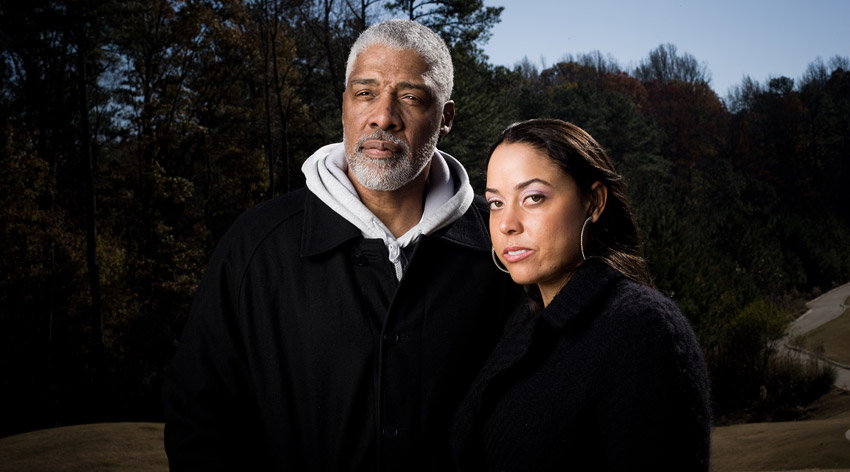

A small crowd quickly formed while they spoke in hushed tones. Jordan's agent, David Falk, held the arm of a young client, Walter McCarty, as if he were a child witnessing history. And in the midst of all this came the Doctor -- tall, distinguished and prematurely gray -- from his broadcasting duties with NBC. He stood watching on the perimeter with the rest of us, and nobody turned to notice.

That was a sad moment for me, having grown up thinking of Erving as the coolest athlete on earth. In that vein, the film was enjoyable, effectively making that case with some wonderful old footage. But the problem with NBA-TV -- and comparative networks spawned by the sports industry -- is that they are promotional vehicles, first and foremost. They invariably will fall short of ESPN's 30 for 30 series, HBO sports films or independent-produced like "Lenny Cooke," recently shown at the Tribeca Film Festival (disclosure: I have a small role in the Cooke film). http://variety.com/2013/film/reviews/tribeca-review-lenny-cooke-1200480441/

That is why, the Erving documentary was also disappointing, falling short of mastering complexity and hard truth.

In 1999, Erving made the biggest splash of his post-playing life when it was reported by a newspaper that Alexandra Stevenson -- a young tennis player who had made an early summer breakthrough at Wimbledon -- had been fathered out-of-wedlock by Erving during his playing days in Philadelphia. He had supported Stevenson but did not have a relationship with her. Several years later, ESPN's talented feature writer Tom Friend did a scintillating piece http://espn.go.com/espn/eticket/story?page=drjandalexandra about how father and daughter had begun to make up for lost time. The story was emotional and heartening. It made Erving stand that much taller.

While dealing with the tragic drowning death of Erving's son, Cory, and how -- according to Erving -- it affected a marriage that eventually dissolved, the NBA-TV film also failed to note that he had fathered another child out-of-wedlock, a son, and later married the mother of that child. Life does take strange turns; this is no attempt to judge Erving, who typically left us believing him to be a caring and decent man. But the omission of Stevenson from the film was glaring for two primary reasons:

One, it was a sensational news story that most NBA fans would probably recall.

Two, the start of a new relationship with a daughter who had previously lived in the shadows would seem to have meshed with Erving's stated credo that he was not a superstar living in the past. And, in fact, believed his best days were still to come.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed